.png?width=2240&name=Austin%20Ads%20(10).png) This is Part 3 of a 4-part series on Blind Rivets

This is Part 3 of a 4-part series on Blind Rivets

In part one of our series on blind rivets, we briefly looked at their history and discussed the two most important considerations to maximize joint integrity: Grip Range and Hole Size. In part two, we broke down the importance of material and tooling as they pertain to joint integrity, as well as the specifics of blind rivet selection. If you have not yet read either of those posts, click HERE for part one and HERE for part two.

In this post, we'll talk about the most common rivet types and their functional differences.

There are two common blind rivet types: Drive-Pin and Break-Stem.

Drive-pin blind rivets have a partial hole in the body and a mating pin that protrudes, positioned in the hole. The installer hammers the pin into the rivet body so that it's flush with the top of the rivet head. One of the significant benefits of a drive-pin rivet is that no special tools are required for installation. You can literally use a hammer if you wish. Drive-pin rivets can also be used with almost any material and don't require a hole to be drilled all the way through to insert. A drive-pin rivet's disadvantage relative to other types of blind rivets is that a backing block may be needed for installation depending on the material and application, which mitigates the benefit of blind installation. They also offer less clamping force than most other rivet styles.

As Assembly magazine explains, "Increased use of composite materials, such as plastic, fiberglass, and plywood, has  increased demand for blind rivets with different upset styles to fasten those materials." These rivets are known in the industry as Trifurcating blind rivets. Have you ever used what's known as a "molly" fastener to hang something in drywall? It's the same concept. The trifurcating blind rivet body has slots in the shank which form "legs" during installation. These legs provide clamping force while spreading the clamp load of the rivet, which is essential when using them in ductile materials such as plastics. They prevent pull-through of the installed rivet in applications where standard blind rivets would fail.

increased demand for blind rivets with different upset styles to fasten those materials." These rivets are known in the industry as Trifurcating blind rivets. Have you ever used what's known as a "molly" fastener to hang something in drywall? It's the same concept. The trifurcating blind rivet body has slots in the shank which form "legs" during installation. These legs provide clamping force while spreading the clamp load of the rivet, which is essential when using them in ductile materials such as plastics. They prevent pull-through of the installed rivet in applications where standard blind rivets would fail.

There's another type of blind rivet known as a "peel rivet." A Peel rivet employs a similar concept as the trifurcating rivet, with a slightly different mechanism. With Peel rivets, the mandrel is made with "knife points" under its head, designed to split the rivet body into four sections upon installation. Those sections then expand and peel back much like the petals of a flower. These "petals" on the backside of the rivet provide clamping force, which is spread out similarly to the trifurcating rivet. Care should be taken when using peel rivets, as sharp edges are part of the formation. Ideally, there should be no access to the backside of an application where peel rivets are installed.

with a slightly different mechanism. With Peel rivets, the mandrel is made with "knife points" under its head, designed to split the rivet body into four sections upon installation. Those sections then expand and peel back much like the petals of a flower. These "petals" on the backside of the rivet provide clamping force, which is spread out similarly to the trifurcating rivet. Care should be taken when using peel rivets, as sharp edges are part of the formation. Ideally, there should be no access to the backside of an application where peel rivets are installed.

Plastic blind rivets work essentially the same as their metal cousins. They require their own installation tooling and tend to dry out and get brittle over time, so careful consideration should be taken when selecting them for your application.

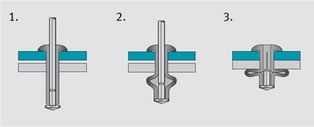

The break-stem type rivet has a hollow core body with an integral mandrel. These can also be further broken down into four sub-styles: Open-End, Closed-End, Self-Plugging, and Structural.

Open-end blind rivets are by far the most common. These are the blind rivets that are typically referred to as "pop" rivets. An open-end blind rivet retains a small portion of the mandrel within the rivet body after installation. This "mandrel head" doesn't add structural integrity to the rivet; however, it helps form the backside of the rivet. It also aids in generating pull up. It also doesn't provide any sealing characteristics to the blind rivet. This style is ordinarily used in lighter, non-structural applications.

Closed-end blind rivets use a solid-core rivet body, thus eliminating moisture or gases' ability to pass through the rivet body itself, which happens with open-end blind rivets.

Examples Of Open End & Closed-End Rivets Can Be Seen Here:

Self-plugging blind rivets refer mostly to "multi-grip" versions. These variants of the standard open-end blind rivet employ a slightly different mandrel head and rivet body design that results in the mandrel stem plugging the hollow body core with a larger portion of the stem. An interference fit results between mandrel and rivet body, essentially preventing moisture and gases from permeating through the rivet body. However, like open-end blind rivets, the larger retained stem doesn't normally add to the rivet's structural integrity.

A blind rivet is deemed to be "structural" when it meets the following criteria: the stem must break flush with the rivet flange (or head) in the minimum and maximum of its grip range, and the stem must be mechanically locked so that it cannot vibrate out of the rivet body after installation. The locked stem thus provides more structural integrity to the rivet, primarily with significantly higher shear values.

There are many different types and styles of structural blind rivets available - too many to list here. We'll break those down for you, along with other variations of blind rivets, in part 4 of this series.

If you have any questions about using blind rivets in your application, contact your nearest Austin Hardware® location to discuss the options.